Happy 2024! We’re pleased to share Issue #3 of The Hum and kick off a new year of ideas, perspectives, and (possible) solutions for sustainable change in the music industry.

If this is your first time reading, The Hum is a newsletter offering insights into the intersection of music, sustainability, technology, and innovation. We started this newsletter to understand the social, cultural, and environmental impact of the music industry and its ongoing evolution. The Hum is edited by Fernando de Buen and Roxanne Hoffman, strategic designers who care about the planet and value the warm sound of a vinyl record.

In issue 2, we touched upon the tensions in the industry such as regulation against digital service providers, green touring plans and fans’ expectations, and the challenge for small musicians to be financially viable.

In this issue we will focus on new possibilities. We discuss how leaders in the industry, such as Warner or Universal, could turn challenges into opportunities in their 10 year plan. We highlight what sustainable design might look like for instruments and listening products. Lastly, we move to part 3 of our history of portable audio, a turning point for music culture and democratic listening.

New sonic aesthetics

As product designers gain more awareness of their influence on the planet, they are incorporating more sustainable principles into their work. But what does sustainability look like for instruments or listening devices?

Here we cover a few select examples:

Biodegradable

In 2019, Aivan, a Helsinki-based design studio, came up with Korvaa, the “world’s first microbe-grown headset.” The prototype features bio-based materials like fungus, bioplastics, and protein-based spider silk. This studio has focused on the similarities of biomaterials to synthetic materials to envision an alternative to headphones, which are all too often easily disposed of.

French luthier Rachel Rosenkrantz creates bespoke guitars using biomaterials as a reaction to the harm guitar manufacturing has historically had on some tree species. Atelier Rosenkrantz features guitars made with honeycomb, mycelium, kombucha leather, and other unusual materials. Rosenkrantz is aware of the unconventional nature of her designs which inherently sound different than traditional forms. But, to her, that difference may be an advantage: “If we want to create new sounds, we might look into new materials.”

Sustainably sourced

Deforestation has had a major impact on guitar manufacturers, leading them to find alternatives for their traditional tonewoods. In response, guitar makers Martin and Taylor are developing their ecological policy. Martin’s OM Biosphere guitar may look a bit colorful, but maintains the same traditional design as their classic guitars.

Similarly, Houd Sounds, based out of Colombia, and House of Marley, originally from Jamaica, use sustainably sourced wood for their personal speakers. While House of Marley incorporates wood with other recycled metals and textiles, Houd Sounds uses no other components (or energy) in order to naturally amplify sound from a smartphone.

Transparent

Fast Company recently shared how designers are trending back to clear tech. Music related designs, like Apple’s Beats Studio Buds+ and Korg’s microKORG synth crystal edition might influence other gear makers to start making enclosures transparent. But, why might transparency matter for sustainability? Although it’s not an explicit goal of these designers, to some degree seeing inside products leads to questions about what they’re made of and serves as a passive means of educating users.

Circular

Morrama and Batch.Works have teamed up to create Kibu, a children's headphones that can be easily assembled, repaired and recycled, creating a circular design product. While a lot of music instruments inherently embody a lot of circular economy principles (repairable, reusable, modular), Kibu is one of the first and few projects designed with circularity in mind, hopefully setting a precedent for other manufacturers.

Integrated

Yamaha’s Design Laboratory has been exploring piano designs that reimagine new ways to integrate the piano into its surroundings. During last year’s Milan Design Week, the company also shared experiments to reimagine how music accessories could better fit into player’s lives. Their approach seems to be to create beautiful and functional objects of music, as well as imagine new ways of interacting with audio.

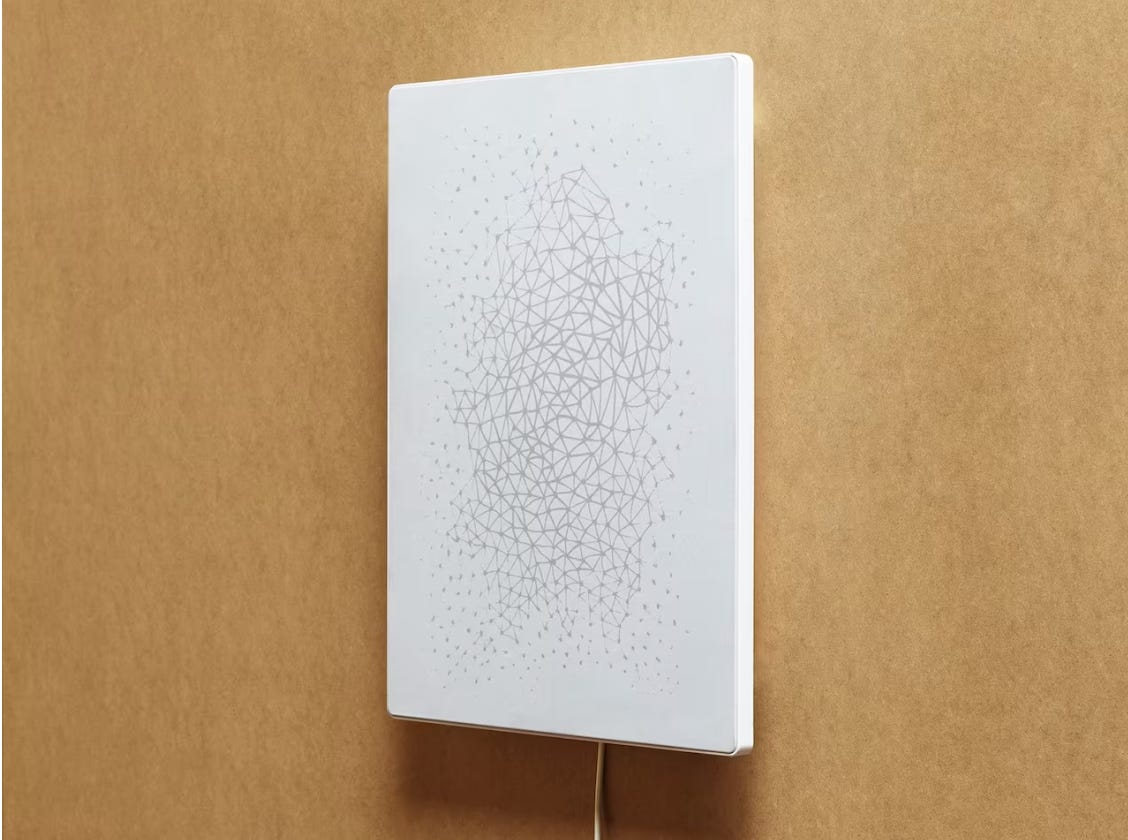

On a different end of this spectrum, IKEA has partnered with Sonos (and previously Teenage Engineering) to create products that integrate speakers into other home decor products, such as a lamp or picture frame. Their approach seems to be to make the speaker “disappear” into the environment.

In the news: Major labels push to increase the value of music

This past week the CEOs of two major labels, Warner Music Group (WMG) and Universal Music Group (UMG) sent internal memos outlining their strategies for the future. Among other priorities, both companies appear to focus a portion of their upcoming efforts to increasing the value of music and to developing superfan-artist relationships.

The conversation around the value of music in the age of streaming is not new, and both these leaders had previously spoken about it. UMG’s CEO, Lucian Grainge, had established an effort to increase the value from streaming in 2023, for which he hailed Spotify and Deezer’s recent announcement of a two-tier royalty system as a success.

These efforts to increase the value of music are generally celebrated across the industry. While issues remain with streaming royalty models, it’s encouraging to see prominent voices in the space advocating to get artists paid more for their work.

It will be interesting to track the effect of labels' push for increased music value on the broader artist ecosystem. As we have mentioned in our previous issue, new royalty models for streaming can be good, but more can be done to prevent leaving emerging and DIY artists behind.

Tracing the history of portable audio

In this series we explore how portable audio changed the way we listen to music enabling it to become ubiquitous, intimate, and easily shareable. Read more about why we choose to tell its story in our first issue.

In our last issue, we gave a brief history of the portable (or transistor) radio and how its influence set a precedent for the personal devices we use today. However, another format led audio to new levels of portability and became a vehicle for music culture cross pollination, magnetic tape – specifically that housed in cassette tapes.

Video magnetic tape killed the radio star

Magnetic tape audio recording was first developed in Germany in 1928 by Fritz Pfleumer and patented as a “sound paper machine." In the 1950s, the Ampex corporation patented several tape head designs to be used for commercial music recording and later film and television recording masters. Even Bing Crosby invested in Ampex, leading to further development of reel-to-reel tape decks that some consumers began using at home. But, truthfully, the reel-to-reel was not a portable audio device. The next advancement for portable audio came from Bill Lear, an inventor who was looking to design a tape system for his aircraft business Learjet. In 1964, the 8-track format was created by a consortium headed by Lear which included audio technology corporations like Ampex and RCA, but also car companies such as Ford and GM. Because he collaborated with the automotive industry, 8-track players were incorporated in car stereo systems while retaining remarkable quality. Just two years before the 8-track, the compact cassette was conceived by Lou Ottens of Phillips but it wasn’t until the mid-80s that the cassette surpassed the popularity of the 8-track and vinyl records.

Given that the medium of magnetic tape had not greatly changed from the reel-to-reel, there were other critical factors that led to the rise of the cassette over prior audio formats. The first being standardization: as a means of promoting the cassette, Phillips waived royalties to enable anyone to license the cassette design for free as long as they adhered to their quality-control standards. By using a shared standard and reducing the size of the form factor to fit the palm of your hand, record labels could easily duplicate pre-recorded audio at scale using less material. Another effect of standardization was that various companies manufactured (and continue to manufacture) blank cassettes consumers could record on, resulting in the birth of the mixtape. The ability to not only read but to write onto cassettes changed the way music was exchanged, particularly for censored or underground music scenes. From disseminating 1970s Egyptian sha’bi music in a gatekeeping political climate, to the self-promotion of 1980s budding hip-hop and rap artists, the cassette was a means to accessing culture and—as Hua Hsu states in ArtForum—“inaugurated an era when it was possible to control one’s private soundscape.”

The experience of listening on-the-go back then and with today’s devices were transformed by the Walkman, first catalyzed when Sony co-founder Masaru Ibuka asked his designers for a way to listen to opera while walking. The Walkman afforded the same mobility as the Regency TR-1 transistor radio, but with built-in privacy as few other tape players incorporated headphone jacks. Sony initially projected to sell about 5,000 units a month, however, the Walkman sold upwards of 50,000 in the first two months.

While the cassette was surpassed by digital media—which we’ll cover in the next issue about the dawn of the CD-ROM—tapes along with vinyl have seen a resurgence in the last few years. Whether big artists like Harry Styles or DIY independent labels such as Gnar Tapes, the industry is taking notice and new cassette player makers like Rewind, or repairers like Retrospekt, are on the rise.